As a youngster, Hannah Peters spent a lot of time in the darkroom at her local college as well as playing hockey and tennis — yet she didn’t think that marrying those passions could make a sensible career choice. “I wanted to do sports physio down in Dunedin,” she says, “because I love sport and wanted to be involved with teams somehow. But one Christmas my uncle told me about Andrew Cornaga [from photo agency Photosport] and said I should go check him out. Until then, I didn’t think sports photography was a thing! I thought photography was all either studio work or weddings, which I didn’t really want to do.” Andrew, it seems, asked the young Hannah to go out, shoot, and bring back the results. “I found some running races or something around the waterfront and shot it.” When asked if it was genius at first go, Hannah replies, “No, it was really bad stuff. It wasn’t good at all!” Yet, when Hannah had had some practice, “They offered me a job. I learned on the job by being dropped in the deep end: looking through heaps of transparencies, editing other people’s work, which was probably the best way to learn — just getting out and doing it as well as making heaps of mistakes.” What ensued is a career that has seen Hannah travel the world following some of New Zealand’s most iconic sportspeople and sports teams as well as a smattering of heavy-hitting international ones — the All Blacks one week, Serena Williams the next. So, how does she do it?Anne Noble is one of Aotearoa’s most distinguished contemporary photographers, recognised internationally for her diverse practice in and meticulous investigation of photography. Her subjects have ranged from the vastness of the Antarctic continent to the intimacy of her daughter’s childhood. But for some time now, a new subject has come to occupy Anne’s attention; Apis mellifera, or the European honey bee.

For over a decade, across several continents, through varied processes, Anne has been investigating the ways in which photography might help us connect with the enchanting and vital world of bees. The impetus for the photographer’s apian interest started in her own backyard, when an acquaintance introduced a hive to her garden in aid of pollinating fruit trees.

“Over a few years, I became the beekeeper and that initiated a real interest and fascination with the bees,” Anne explains. “Those things that I am interested in and come to know and to love, I have this desire to bring those into my work.”

And bring the bees into her work she did. From 2012, Anne has immersed herself in the world of bees, connecting with beekeepers, bee clubs, farmers, scientists, artists, and educators around the globe to investigate ways of representing the unique life of the hive in photographic form.

“Being a photographer and working in a variety of ways the challenge was, ‘How can I photograph something that is so difficult and small and intriguing?’ It raises all sorts of questions around the environment and our relationship to the natural world.”

These tiny insects led the artist to massive questions about the impacts humans are exerting on the world that sustains us. Bees are an indicator species, meaning that whatever shape they are in is reflective of the wider environment. Threats to global biodiversity, the use of pesticides, effects of industrialised agriculture, and cultivation of vast monocultures are all contributing to the decline of these creatures upon which our survival depends.

From the tiny hive life of bee society to looming existential threats, the photographer has pulled focus on a complex subject ripe for her style of in-depth conceptual investigation.

The phenomenon of swarming occurs when a colony of bees splits, with up to half of the colony’s bees leaving home to find a new residence, moving through space as a single-minded cloud

of humming organisms. It is a spectacular sight

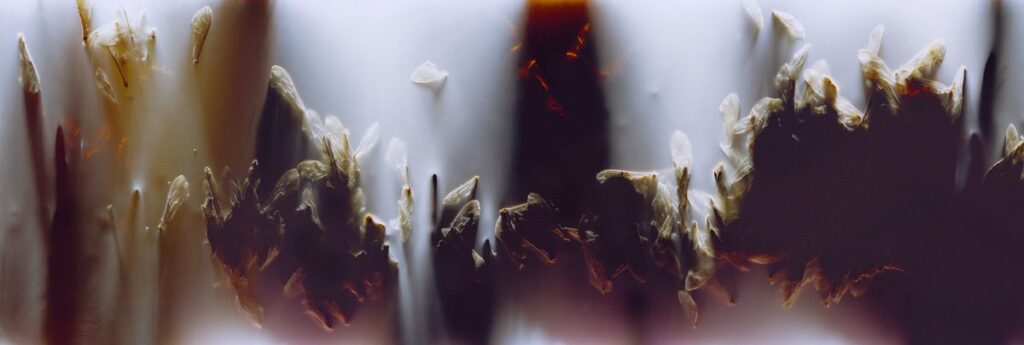

to behold and unsurprisingly captivated Anne when a portion of her hive first relocated to a nearby po- hutukawa tree. In the hopes of experiencing more swarms, Anne went to the local bee club and put her name on their ‘swarm catching list’, a directory of people who are available to catch, rescue, and relocate a swarming colony. But it wasn’t until she connected with Dr Guy Warman, associate professor in the Department of Anaesthesiology at the University of Auckland, that the photographer got her first real opportunity to photograph a colony of bees en masse. Warman’s research involved anesthetising a hive to examine the effect of controlled loss of consciousness on the cycle of the circadian rhythm in relation to light and time. “When he described it, I had this fantastic image of ten thousand waking bees,” Anne recalls. “It was a purely poetic response to a scientist’s really serious investigation into the impact of anaesthetics on the human biological clock.” A hive is never still, but through Warman’s experiment Anne was able to train her camera on a mass of slumbering bees, waiting for the moment the air returned to the hive and they stirred, woke, and began to move. The resulting images, collected in the series Song Sting Swarm, present landscapes of tiny bodies, intricate wings, and microscopic hair, packed impossibly close together, filling the entire frame. It is an entrancing sight that confounds superficial notions of our connection with nature. “We often see ourselves as ‘apart’, as the pinnacle species — we manage and control everything else,” Anne says of humanity’s self-image. “It’s a rather mistaken view. Looking at and learning about something like a colony of bees is a very humbling experience.”

In 2014, Anne embarked on a Fulbright scholarship at Columbia College in Chicago, where she was able to further her bee experimentations. At the time, a phenomenon called colony collapse disorder — in which the majority of honey bees in a colony disappear — was taking a toll on the commercial beekeeping industry. One suspected cause of such collapse is the use of pesticides. After connecting with a local bee club, Anne was made aware of a beekeeper who had just lost all of his bees to the drifting of pesticide from adjoining farmland. As any inquisitive artist would, Anne requested one of the dead colonies be put on ice, which she then picked up and relocated to her own freezer. She now had around 10,000 dead bees to contemplate. “I thought I could pluck and collect the wings. It seemed like a nice metaphor to play with; these will never fly, never lift an organism, and yet they remain intact. A bee’s wing is a very fine, beautiful thing.” Ever ready to experiment with process, Anne decided to use the wings she had meticulously plucked over a series of evenings to create photograms, photographic images made without a camera by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive material. Where the object is usually laid flat under a piece of glass, she decided to spread the wings across a metre of 120 film, roll the film, and hold it in her hand. “I had the film carefully inside my hand with the light coming through my fingers — it was like I was using my body as a camera. I turned myself into the photographic device.” After gently returning the wings to their tray, she processed and scanned the film, and produced striking prints that stream down vertically to reveal a fascinating abstraction of intricate shapes and surprising colour. “There’s no camera, there’s no lens, no machine; it’s just the light and chemical sensitive medium, the wings, and the human body. But they’re extremely photographic, the sense of form and the tracery.” The series, first exhibited in France, was titled Bruissement, a French term with no direct English translation that invokes the airy rustle of leaves or the softest sound of wings.

Images (top): Bee Wing Morphology #1 and #3. (Bottom) Eidolon #3 and #5. All images by Anne Noble.

Anne was far from done with contemplating the exquisite wings of bees and her collaborations with scientists would also continue. Keeping her feelers out for researchers interested in the phenomenon of swarming, the photographer was invited to visit a large agricultural university in Texas. “I’ve always been interested in dialogue and conversations with scientists, I love the questions they ask and the ways they go about asking them. Artists, we ask very different questions — we are interested in metaphor and uncertainty. Scientists are trying to find answers to quite specific questions.” At the Texas A&M University, Anne happened upon the work of a scientist who had been asking a very specific question indeed: Over a period of time they had amassed a large collection of bee wings as a morphological study (relating to the size, shape, and structure of animals) that asked if the reflective qualities of light on a bee wing were specific to different species of bees. “I was going, ‘What? You’re looking that closely?’” the photographer exclaims. “It was the absurdity of the question — and here I was, working with bee wings, doing something equally absurd.” Being granted permission to use these masses of bee wings, Anne got to work in the laboratory creating what would become two separate bodies of work. The lab had a “beautiful little lighting kit”, which Anne combined with her macro lens and the light of her mobile phone as a backdrop to create something of a photographic microscope. “I really had a wonderful time over a couple of days, playing, imagining I was both artist and a quasi-morphological scientist doing art,” she says with obvious joy. Some of the images made here would comprise the series Eidolon, colour prints that examine the patterns of light as it passes over the blown-up details of various bee wings. The second series, A Bee Wing Morphology, was created when Anne returned to Columbia College, Chicago, where she and a faculty member used the images to create tintype photographs of the wings. “I really love opportunities to play with antique technologies,” she says. “We spent a lovely time scrubbing plates, hand-coating the plates with gelatine, drying them, hand-coating them with light-sensitive material. It is really working with a plate to create a large print surface.”

Zooming out ever so slightly from wings to a full bee view, Anne connected with yet another scientist in France to create what would become her Dead Bee Portraits series. Once again in a laboratory, learning a new process, Anne utilised a scanning electron microscope to create monochromatic images that cast the body of the bee in a statuary mode. You can’t put a live bee in the mechanism of an electron microscope, so the photographer was working with dead bees — in a hive full of around 70,000 bees, there will likely be mamy bees dying a day, at the end of their natural lives, so they are not difficult to come by. “The process fascinated me,” she enthuses. “You ‘sputter-coat’ the bee in a molecule-thin layer of gold, so I have a golden bee that is placed inside the chamber of the microscope and there’s an electronic beam that gathers data points to activate the image. That molecule-thin layer of gold that is completely covering the bee is responsive to the electronic beam.” The process produces an image on a screen, which the photographer was able to control. It was powerful enough to zoom in on the microscopically fine hairs of the bee’s antennae, but Anne had the idea of using it to create something more akin to a photographic portrait. “If you look at the wings, there is no transparency; it is the digital mapping of a surface and they look kind of grey, like leather almost. They look like they are covered in dust. That then prompted me to think about the idea of them being dust-covered objects from a future time. If you were to imagine a world without bees, we might forecast these images into a museum that is celebrating a species that no longer exists.” Photographs made without light, seemingly dust-covered figures imagined as monumental sculptures; Dead Bee Portraits is a series that speaks to a potential loss in a future we can only hope to avoid.

Anne would soon pivot from ruminating on death to a celebration of life, setting herself the ambitious task of creating a photograph that was alive inside. In what might be considered the culmination of her photographic entanglement with apiculture, she set out to conjure a physical structure or sculpture that would support the life of a hive while presenting it in photographic fashion within a gallery space. So was born Conversa- tio- – A Cabinet of Wonder, an ornate wooden cabinet that, when opened, reveals a thriving hive of bees within its photograph-like frame. The result of collaboration with experts of all kinds — beekeepers, scientists, a cabinet-maker, educators, and gallery staff — the work was originally created in France and built again for 2018’s Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. Anne worked with Professor Srini Srinivasan, an expert on bee navigation at the Queensland Brain Institute, to design the integral tunnel that would allow bees to fly into the hive from outside the gallery. They were determined to create something that was both functionally fit for the bees as well as being visually arresting. “It was a really beautiful thing to see,” the photographer says. “When the cabinet was closed, you didn’t see the colony of bees but you could see their shadows on the wall as they flew down their entrance.” The doors of the cabinet would be opened four times a day so that visitors could view the frame as it filled with a colony of bees, their brood, and honey — all signs of a happy hive — over the five-month duration it was installed. For Anne, it was a way to assist in transforming people’s understanding of the world through the appreciation of bees. “It’s all very well to ruminate on dead bees, but there is nothing more wonderful than a colony of bees themselves.” All of these captivating bee projects, and

more, are collected in Anne’s latest book,

Conversa- tio- – in the company of bees, from Massey University Press. Every bit as visually enthralling as you would assume, the publication goes beyond the photobook form to include writings, correspondence, and conversations with some of the many and varied experts in Anne’s hive of collaborators. It is a singular book that truly reflects the range and depth of the photographer’s inexhaustible curiosity.

For more information on Anne Noble’s Conversatio – in the company of bees publication, visit Massey University Press at masseypress.ac.nz

Copyright © 2025 Federico Monsalve Limited. All rights reserved.