Words: Adrian Hatwell

Photos: Vanessa Green

We have a rich tradition of social documentary photography in this land, and the subgenre has been instrumental in recording pivotal moments of Aotearoa’s modern history. As well as capturing events of historic importance, our social documentary photographers have kept their eyes on daily life and seemingly mundane subjects.

As a result, we are now fortunate to have a legacy of imagery that captures New Zealand’s biggest moments as well as a record of diverse everyday existence throughout the decades.

At the present day end of this legacy is where we find Auckland photographer Vanessa Green. A relative latecomer to photography, in just seven years Vanessa has established a practice that encompasses both big and small of social documentary shooting, while eking out her own unique groove in that still-unfolding narrative.

“My biggest goal is for my personality to come through in my images,” Vanessa tells me as we meet to chat at a local Grey Lynn cafe. “My images are what give me a voice, because otherwise I’m quite a nervous speaker. I use photography as a way to build a kind of view of myself.”

Vanessa’s images are a flood of faces and spaces — many that will be familiar to those who dwell in Ta¯maki Makaurau’s central fringes. Artists and entrepreneurs, architecture and decor, natural spaces and urban constructs, friends and strangers — Vanessa’s subjects are the very elements comprising the photographer’s own life, and she strives to capture them with as much authenticity as possible.

“What my eye is drawn to is the here and now, and the simplicity of life,” she explains. “What I’m most drawn to is people and their spaces. My aim is to create a really accurate description of people in their own environments.”

Now nearing 40, Vanessa didn’t seriously pick up a camera until her early 30s. Although she became a photographer later than many, Vanessa tells me she has always been a very visual person with an observational curiosity towards her surroundings.

Most of her life has been lived in Auckland, but Vanessa has spent time in London, using it as a base from which to explore Europe, Asia, and India, before returning home to Aotearoa. She describes this pre-photography experience as her “background in exploring the world”.

As she entered her third decade, Vanessa found life in need of a shake-up. A fateful course at Auckland’s Unitec institute would prove just the solution, opening the door to a new passion for photography.

“I had recently lost my dad and had come out of a serious relationship; I needed something to focus on. I needed to make a shift and I’m grateful to have fallen into a practice that has become part of my everyday life. It’s consuming.”

The course gave Vanessa a chance to reconnect with film photography, a medium she hadn’t dabbled in since foundational learning back in school. She enjoyed rediscovering the slowness of analogue cameras and the rawness of negatives. It also gave her a link to the social documentary photographers of the past who inspired her, such as Ans Westra, Marti Freidlander, Gil Hanley, and John Miller.

“The way that our country has been documented has been amazing, and I just hope my work can add a little to that.”

An affinity for the darkroom has allowed Vanessa to connect with a number of like-minded contemporaries in the Auckland region. Together they make up the CarWash Collective, a group of photographers who support each other in their individual practices and exhibit together — D-Photo readers will be familiar with members Tim D, Petra Leary, Brendan Kitto, and Todd Henry from past coverage.

“I’m very lucky to have people in my world who are very giving with their knowledge,” Vanessa says of the group. “They’re very enthusiastic photographers and very encouraging with everyone’s own practice.”

With an awareness of the photography giants she follows and a crew of fellow travellers supporting her, Vanessa now roams the city capturing the urban strata with a quiet passion and unobtrusive craft.

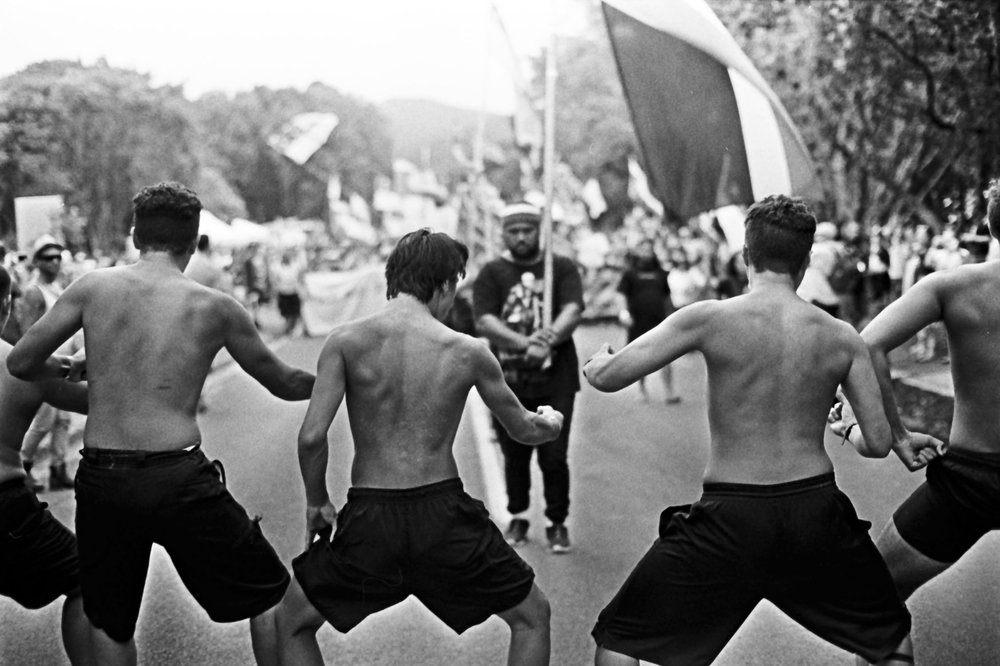

Like many of the social documentarians before her, she has often found her lens pointed squarely at the people in her community standing up for their beliefs. Instances of protest and civil disobedience have long attracted some of Aotearoa’s best photographers, and Vanessa has been on hand for such Auckland uprisings as the Black Lives Matter march and anti-Asian hate protests.

“I document it because I’m there. It gives an understanding of who I am.

“I love that people are passionate about their causes. It’s a big part of our history, and it always has been, to have a voice on the issues in our country.”

Vanessa is quick to note that she does not really consider herself a ‘protest photographer’, these photos making up just a small part of her overall output. The images do indeed appear as isolated instances of loudness in a portfolio dominated by the photographer’s innate ability to evoke the softer, quieter aspects of life.

The big moments definitely have a part in shaping our world, but it is perhaps the unremarkable constants of our daily lives that have the biggest role in creating our realities. This is the milieu Vanessa clearly loves to play in: the geometry of street signs and window arrangements, the shape of a loving couple’s embrace, the unique geography or a hand hard at work on its craft. Vanessa does not so much bring her world to us, as offer us a beautiful new way to consider our own.

Whether shooting an environmental portrait inside someone’s workspace, a barren streetscape dominated by graphic architecture, or the subtle play of light across a range of untouched hills, each image is imbued with something personal to Vanessa, creating surprises from the familiar and familiarity in the alien.

“My biggest aim is to accurately document parts of my environment and surroundings. I often photograph friends, or friends of friends, or things through a connection of some sort. I’m also drawn to space and something that evokes a nostalgic feeling for me, very New Zealand specific.”

Throughout a diverse portfolio, one of the most constant elements of Vanessa’s photography is her clear connection with people. Be it a staged portrait or candid street scene, the photographer seems always able to coax out a sense of relaxed openness from her subjects.

Vanessa is never found without a camera strung across her shoulder — “it’s as much a part of my life as getting up and brushing my teeth” — and when out in public she’s always on an instinctual hunt for people who interest her with their “vibe”, something she is compelled to try to capture on film in the moment.

“My eye sees so much that I haven’t been able to capture with my camera yet,” she explains. “It feels like a continuing process, and I think that may go on for the rest of my life. It’s OK that I might not ever get to the point that I can portray what my eye sees — but I’m going to keep trying.”

The photographer’s ability to connect with her subjects is most prominently on display in her Home Portraits series. For these images, the subjects have invited Vanessa inside their most personal spaces to have an image created that expresses their unique identities.

“I felt it was an authentic way to capture people, in their own environment and space, rather than moving them somewhere more aesthetically pleasing. It just sat right with me.”

With these portraits, the process of creation begins with the relationship itself. Vanessa has to achieve a high level of trust with the person she is shooting before being invited into their innermost domain.

“I can photograph a little bit more intimately because I can go into their space. Even though the portraits are quite deadpan and straight-on, it’s a big thing for someone to let me into their space and allow me to capture that.”

Through the Home Portraits images, we are invited to explore both the physical identity of the subject and the way their inner life has been projected onto the space around them. Meaningful collections of artefacts and bric-a-brac, the artwork and posters that adorn walls, bookcases jammed with a syllabus of personal passions, workspaces laid out with tools of the trade and inspiration, bedrooms bedecked with cultural pride and family memories.

“I think everyone has an amazing space; it’s just a matter of capturing that — that’s the beauty of it,” says Vanessa.

“People surround themselves with these little things that they love, that they’ve collected, or that are important to them. The little conversations you have with people: ‘I have this little thing here, and I know it doesn’t look like much, but it’s from this person at this time …’

“There’s always a little story; it’s really beautiful.”

In the immediate future, the photographer plans to keep focusing on engaging with people and their spaces, although she does feel her practice may soon pull her in a slightly different direction. Growing up in Auckland, disconnected from the Nga¯ti Maniapoto roots on her father’s side, Vanessa is keen to begin a journey of cultural reconnection — and her camera is bound to play an important part.

“I often use my photography as a tool to help me feel comfortable in spaces that are sometimes hard. I totally think of it as my language.”

Where this compulsion to document people and space will take the photographer, Vanessa remains unsure. But for now she is content to enjoy the fixation, continue building a body of work, and further refine her practice.

“I feel like I’m doing a lot of groundwork, I want to let my work sit for a while. I have my whole life; I don’t want to rush that process.”

Copyright © 2024 Federico Monsalve Limited. All rights reserved.