The plan was to gain a PhD in neuroscience and psychology. However, four years ago Becki Moss took a year off to test the waters of professional photography — something she’d been dabbling in since high school — and she has never looked back.

What began as a self-taught hobby at age 16 — the technicalities of it learned, piecemeal, via YouTube tutorials, friends, and tight-knit Flickr communities — morphed into regular paid gigs to shoot weddings. Seven years of canapes and lubricated dance moves later and the young creative was still passionate about the craft.

“Because of uni I’d been turning down photography opportunities and not really having time for it. I thought, ‘I can go back to my study if I want but I might not necessarily have these opportunities with photography in the future.’ So, I gave myself a year to see if I could do it as a full-time job,” says the affable, 26-year-old, who sports short- cropped hair and big glasses.

This daring plan to swap lab coats for pixels has seen her forge a very busy career in commercial, social, and art photography, with a heavy focus on portraiture.

Does the scientist in her in any way influence her photography?

“No,” she says adamantly, “my photography is very intuitive” — then she pauses for a second and admits that her former focus on psychology does indeed cross over to her passion for photographing people and “trying to understand them” through the lens.

One gets the feeling, however, that Becki’s talent for portraiture is more aligned to personality than any professional training. She has one of those disarming smiles and easy- flowing conversation styles that, as one finds out, has allowed her to photograph people in fairly personal havens and often vulnerable circumstances.

“I always think of my cameras as kind of my passport into spaces,” she says.

That passport has allowed her to enter a myriad of worlds, including corporate branding assignments, science communications projects, and — one of her ongoing passions — spaces where the queer community congregates.

“I’m queer, came out a few years ago, and photographing the community was really kind of my way of connecting with them.”

Throughout the years Becki has captured quite honest, and often raw, portraits of the clubbing scene, although she is quick to point out that these are “not your classic nightlife, smiley photos of people dancing; [they are] very much straight-on photos of people in their haven.

“I try to make people as comfortable as possible. I explain who I am, what I’m doing, and often compliment their outfit because usually they are just incredible!” she says. “Now, more and more people know who I am.”

Becki mentions the importance of being very open and communicative about what she does as a crucial part of gaining trust in what are often very private moments: “because obviously you don’t want to accidentally out someone”.

As influences, Becki quotes the work of Fiona Clark and, in the same breath, talks of UK photographer, Robin Hammond, who has made his career from documenting marginalised groups through long-term visual storytelling projects.

“His work is incredible,” says Becki, “not just the images but the way he talks about his subjects: very empathetic and understanding. He often has to question whether the photos he takes are worth the potential risk to that person. Does it actually benefit them or are they just creating photos for the Western gaze?

“That was something that really resonated with me because I hadn’t really heard photographers talk about that. For me, especially photographing the queer community, it is something I think about a lot. Are these photos worth the potential risk to this person? There are so many incredible images out there but, for me, the intent they were taken with is just as important.”

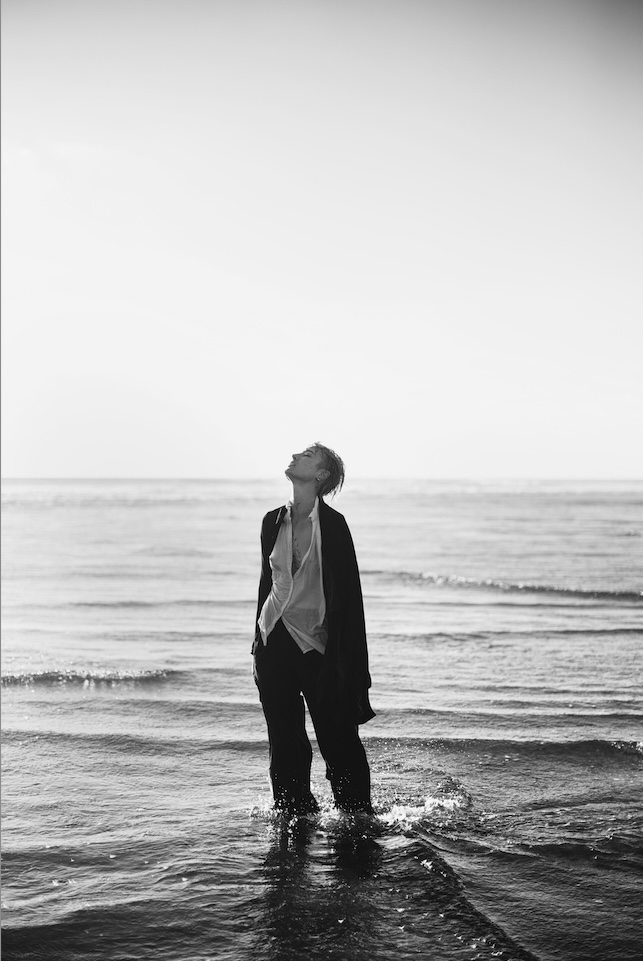

The subject of empathy when confronted with vulnerability is one that Becki quotes often, and one that she has a very personal connection to. The young photographer has lived with chronic kidney disease, endometriosis, and constant pain for some time now. She has documented her own vulnerabilities by often turning herself into the subject of her photos — a process, she says, that has allowed her to have an added understanding of what her subjects might feel.

“I did a project, exhibited last year, called the Masculinity Project, which was photographing men and the places where they felt the most and least masculine, and asking them what does it mean for men to be photographed, and discuss their masculinity with someone who’s a woman, and kind of turning the tables on being a woman and being photographed by men,” she says, “and being in New Zealand, where we have a very strong bloke culture.”

The resulting work is a strong, emotive series about the changing roles of gender and culture in the modern era, a thoughtful and respectful glimpse into very personal moments that, as a collective document, marks a very specific moment in social history.

The young photographer plans to continue her wide interests in social portraiture and combine those with commercial and science communications.

“Working with Siouxsie Wiles would be a dream!” she says.

As for the lab coats? They will remain hanging in storage for some time yet.

Visit beckimoss.co.nz for more of Becki’s work.

Copyright © 2025 Federico Monsalve Limited. All rights reserved.