If you spent any time in Kirikiriroa (Hamilton) in the ’90s, which I did as a primary-aged child, then looking at the photographer David Cook’s new book, Jellicoe & Bledisloe, may feel strikingly similar to catching up with an old but estranged acquaintance. The deep green of ubiquitous Waikato Draught labels, the leering iconography of hair metal T-shirts, flourishes of ’70s decor in its twilight years, the wet geometry of a slickly popped manu – Cook’s medium-format colour photography surveys this time-gone-by with exacting detail.

If you are unfamiliar with the suburb of Hamilton East in the ’90s, do not worry, the book will lose nothing of its appeal to the uninitiated. As a long-form documentary photographer engaged in telling the stories of communities, Cook has honed his ability to guide a reader through the cultural signifiers, relational complexities, and everyday joys of the people and places that he immerses himself in. You’re in good hands and in for a treat.

“I’m particularly interested in finding out what makes communities work, especially communities that are going through some kind of transition,” he says as we speak on the phone. “Doing long, slow storytelling, getting to know people, visiting and revisiting places and people.”

He’s done it with the likes of coal mining townships (Lake of Coal), his hometown of Christchurch (Meet me in the Square), and Wellington’s high-density social housing landscape (City Housing). The works in Jellicoe & Bledisloe were created while Cook was living in the state housing suburb from 1993 to 1997. He was working as a museum photographer, raising a handful of young children with his partner, and hungry for a way to flex his visual muscles that didn’t involve far-flung travel and prohibitive expense. The solution was in his own backyard.

“I was searching for a way of regaining some of that joy I was potentially losing in my photography through a lot of constraints,” he recalls. “I was using a large Mamiya RZ67 camera loaded with film, often with a flash, hand-held, and getting really close to people’s lives.”

And when he says really close, he is not kidding. Readers are given access to domestic scenes of television-watching and meal preparation; we are ushered into the middle of a boisterous neighbourhood party in a converted garage; allowed to peer over the bonnet as DIY automotive work is performed in the front yard; and stand transfixed on the lawn as neighbourhood children practise their handstands around us. All the while, Cook is subtly cataloguing the cultural milieu: the distorted face of Winston Peters on a struggling cathode-ray tube TV; the simple branding of soft-drink labels that exist in much flashier forms today; the collaging of heart-throbs, music idols, and booze favourites on teen bedroom walls.

He recalls being drawn to music, knocking on a door, and being invited in for a drink at a party. He would see children playing in the street and talk to their parents, and be allowed to photograph the play. Sometimes he would spy furnishings through a window that caught his eye (say, giant images of Elvis) and he knew that whoever lived there was likely to be very keen to chat about their clear passion.

That’s how he did it in the ’90s, and it’s still how he’s doing it today. Through his current work in Wellington, investigating social housing blocks, he has found people to be just as receptive to his interest in their lives, as long as he is able to build trusting relationships. Though he admits that, more than 25 years down the path, we have seen shifts in how people relate to photography.

“One big thing that has changed since the ’90s is the presence of a lot of photography on social media, and that means that sometimes people want to be more in control of their own imagery themselves now, and people tend to be more sensitive and aware of controlling the representation of themselves. I think some of that innocence isn’t quite there.”

And that is far from the only thing that has changed since Cook first made the images in Jellicoe & Bledisloe. In recent years he has returned to the suburb he once lived and worked in, hoping to track down some of his subjects — a thorough door-knocking of the neighbourhood revealed not a single resident who had been living there in the ’90s. The council has placed state housing heritage status on the area, so at least many of the houses looked familiar, from the outside at least.

Happily, Cook has since been able to track down many of his old neighbours thanks to an article in the venerable Waikato Times and a measure of judicious Facebook sleuthing. It is important to the photographer that these relationships be built on trust, and there’s significant fondness in his voice when he speaks of the way images from the project live on as parts of cherished family photo albums.

Another aspect that has changed since he photographed his old neighbourhood is the way Cook thinks about the work.

The project began as a way for him to push past the boundaries imposed by commercial work and reconnect with the excitement he first felt about photography while at Canterbury University, learning about the likes of Bruce Davidson, Walker Evans, and Dorothea Lange. It is not difficult to see how successful the experiment was through the loosely kinetic, spontaneously observed, energetically captured imagery. Fences are jumped, beer cans gripped, trees scaled, windshields wiped, candles lit, hair brushed, potatoes scooped — the air of unguarded industry and the vibrant everydayness of the scenes is to be treasured.

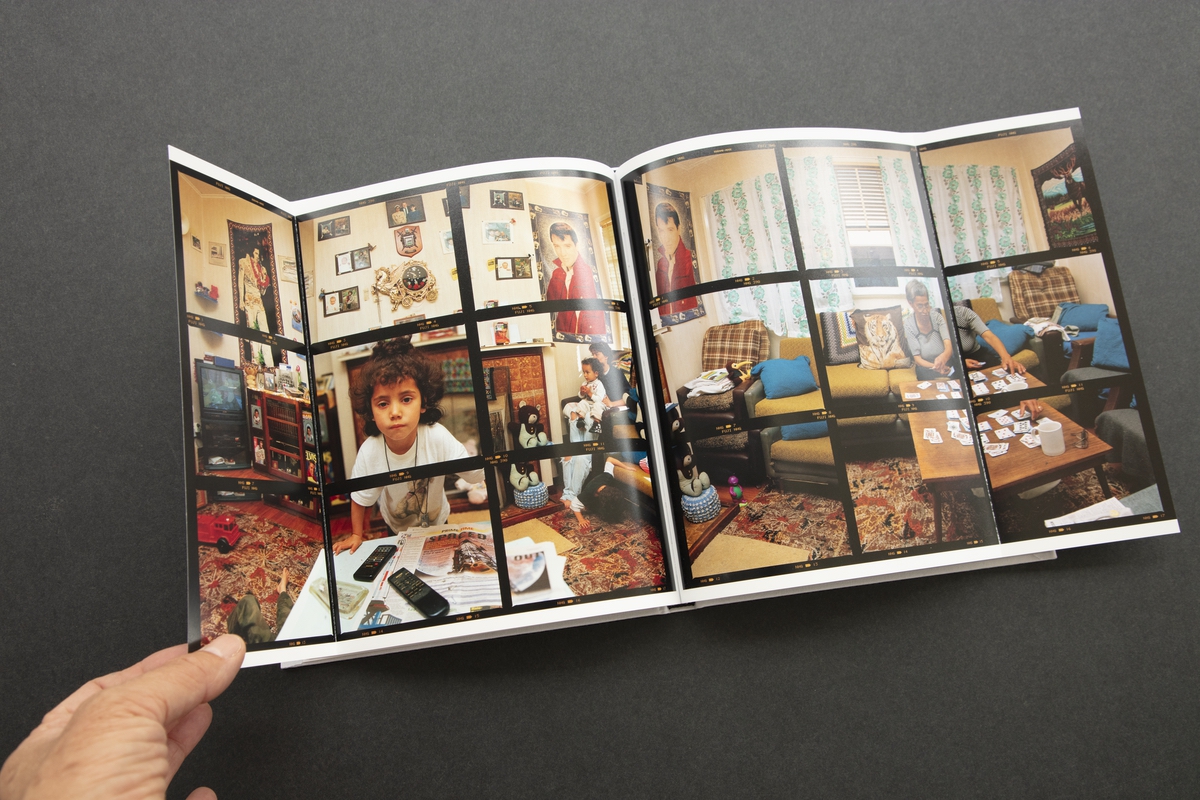

Cook has also found a way to enhance these feelings through the photobook form. Certain images spill from the edge of the right-hand page onto the beginning of the following spread, imbuing the reading experience with an unrestrained, rambunctious flow that echoes the good-natured rowdiness in many of the scenes.

Other spreads fold out from the book, revealing a sprawling image of individual photos in a contact sheet-like grid. Through these you can immerse yourself in the intimate minutiae of a scene: the coverlines of a Skywatch magazine resting on a table; the high-contrast font of Teletext across a TV screen; individual framed photos on a living room wall. Those able to attend the project’s Wellington exhibition, from late-February to mid-May, will be treated to gigantic prints of these particular images, 3.2m wide by 2.7m high.

Another key feature of the Jellicoe & Bledisloe photobook is its relative absence of words. There is no introduction to explain what you are about to see, no captions outlining what it is that each photograph has to offer. It is not until the end that Cook puts his thoughts into text, but it is well worth the wait. It is a candid recollection of making the images as well as a critical revision of the area’s history, including the erasure of rich indigenous history and replacement with colonial memorialising (Jellicoe and Bledisloe are street names in the neighbourhood, named — as with so many others — after British governor-generals).

When Cook lived in the area, he was completely unaware of its rich and significant pre-colonial history. It was not until he returned and received a history lesson from his friend Wiremu Puke (Ngati Wairere) that he was able to access these important stories. The same was true for me as a kid, living and being educated in the area — those stories were not told, because that sort of erasure is one element of how colonialism maintains power.

And that’s something that is also at the heart of Jellicoe & Bledisloe. Yes, it’s illuminating and beautiful and fun. But it is also a call to be mindful of your place in the world, to acknowledge the complexity of your immediate environment, and to appreciate the depth of history that exists everywhere. I think Cook says it best:

“I hope people will see the significance of what it means to look at the richness of the culture we have in our everyday lives, in our own backyards, in our own neighbourhoods. Paying close attention to those stories that are close to home is a big thing for me.”

To view more of David Cook’s work visit davidcook.nz

Copyright © 2024 Federico Monsalve Limited. All rights reserved.